Why I tune guitar with a tuning fork

When I bought my first acoustic guitar, and it was Stagg dreadnough of a spruce, I already had a tuning whistle that's there from my mother’s tourism past. I used it to tune the guitar. But soon I realized that this whistle tone seems doesn't follow de facto standard: if I played backed by some background recording from the Internet, the guitar sounded clearly not in tune. Then I learned that today in music, the “la” standard of 440 Hz is used in the vast majority of cases, although there are exceptions. For instance, during a long recording session in a studio, string instruments slightly tune down. This was the case for the Beatles, when they were overwriting one song like 20 times.

I decided to buy another tuning tune, a fork "la-440". I’m using it to tune guitars since then. Although at the time of buying there was a question - either to buy a tuning fork or... become like majority, using guitar tuner? But the tuning fork was worth a penny, and looked beautiful. Thus I chose it.

And now I am very happy with my choice. Because the use of a tuning fork improves microtonic hearing. If at initially I hardly distinguished, either a string is down by 1⁄4 tone, or the opposite is true, and it's 1/4 higher, but now I clearly hear what the tuner does not hear. Or it hears, but simply misunderstands the data.

I learned how to adjust a 6-string guitar by ear from a teach-yourself book, guitar for beginners. My mother gave me it, this was an excellent book, but then gave it to one person, and he gave it to his friend, ... finally, the book was lost. Maybe it can be found online now. I don’t remember the name of the author though – it was a woman, but what about the name? I don’t remember the book title either. But I clearly remember the method of designating chords in this book. Instead of a traditional approach with the letter of the tonic of the chord and the chord type (like Am7 = la minor septa chord), it used a key-independent form of the chord naming, which I did not see anywhere afterwards. A major tonic triade was recorded as t1, major subdominant chord - as s2, dominant chord - d3, minor tonic chord - m6, 2nd step in the minor - m2, minor dominant chord (harmonic) - t3. I don't remember exactly the numbers, and letters could be different.

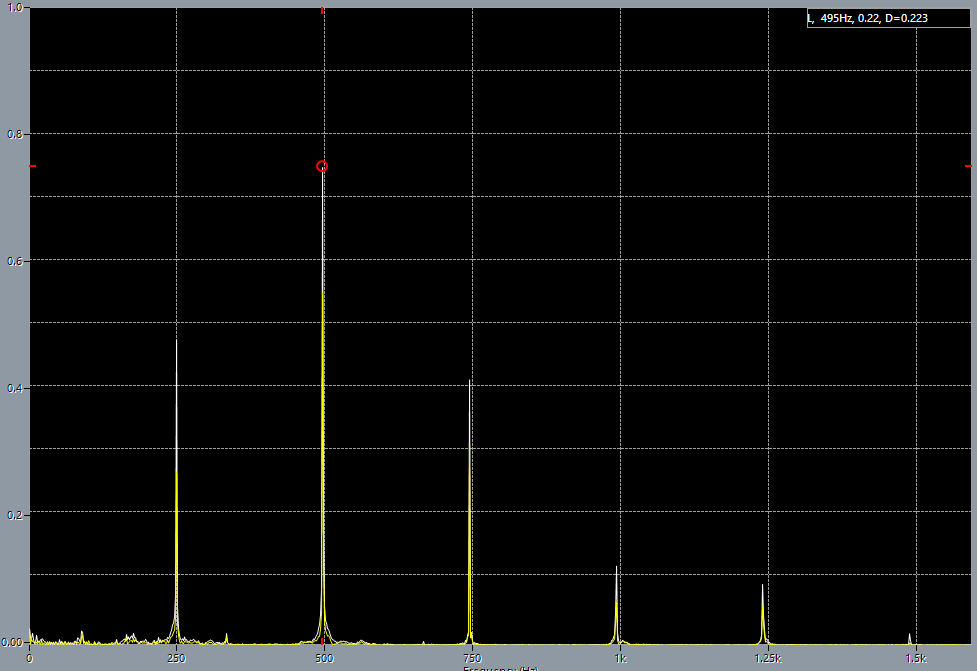

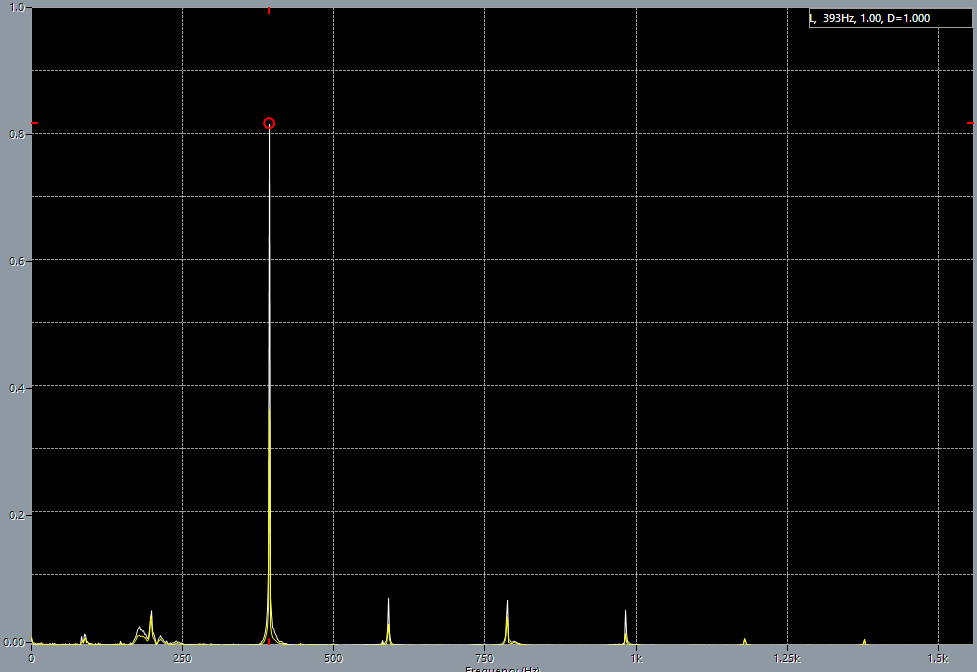

So I tune the first, the thinnest string by the tuning fork - on the 5th fret, and it should sound in unison with a tuning fork 440 Hz. But the tuning fork timbre is completely different! The first lesson is to learn how to hear unison and its deviations for different timbres. But then what is timbre? In short, for any instrument except for an oscilloscope connected to PC speakers, a note does not sound as a naked frequency of 440 Hz. Instead, it consists of 440 Hz and a set of harmonics – that is, the overtones, and the frequency of those overtones is equal to the main frequency of 440 Hz which is multiplied by some natural fraction: 880 Hz (multiplied by 2/1), 1320 Hz (multiplied by 3/1), 220 Hz (multiplieded by 1/2), 82 1⁄2 Hz (multiplied by 3/16), 330 Hz (multiplied by 3/4), 660 Hz (multiplied by 3/2), 1000 Hz (multiplied by 5/4), 1320 Hz (multiplied by 3/1)... In fact, there are usually much more harmonics. The amplitude of each harmonic is unique for a particular instrument, and this combination of harmonics' amplitudes gives a unique timbre to each instrument. And naked 440 Hz just squeak like tamagochi.

When I managed to adjust the first string, it' somewhat easier to tune the second string, since the first two strings' timbre is almost the same. Just hold the 2nd string on the 5th fret, and it should sound in unison with an open 1-st string.

Then the strings with copper winding begin, and their timbre is markedly different from two thin steel strings. Therefore, the 3-th string needs to be carefully adjusted. On fret 4, it should be in unison with an open string 2.

The three remaining thick strings are tuned in perfect fifths, the next string on fret 5 should be in unison with the open previous string.

Thus, we get the EADGBE system. But don't hurry. I give the guitar a minute or two to rest, and check the octaves then. If I have just installed a new set of strings, the guitar tuning will now need to be corrected with a probability that's little bit higher than 98.5%. But how to check the octaves? I just play one note, for example E, on different strings, in different octaves. It should sound clean. Then another note, A, then D, G, B. Until I'm tired.

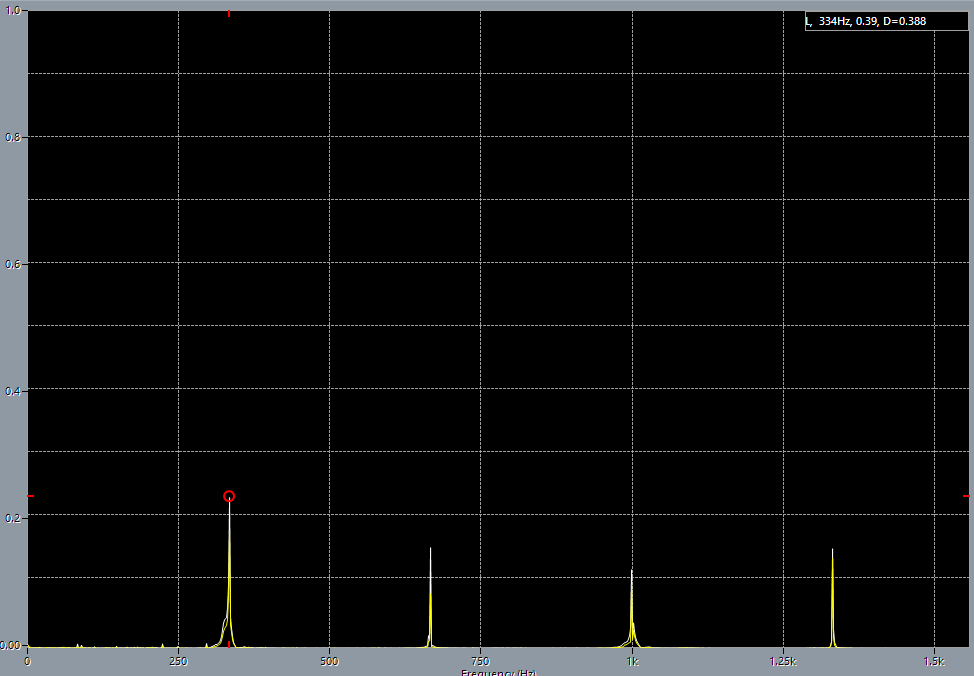

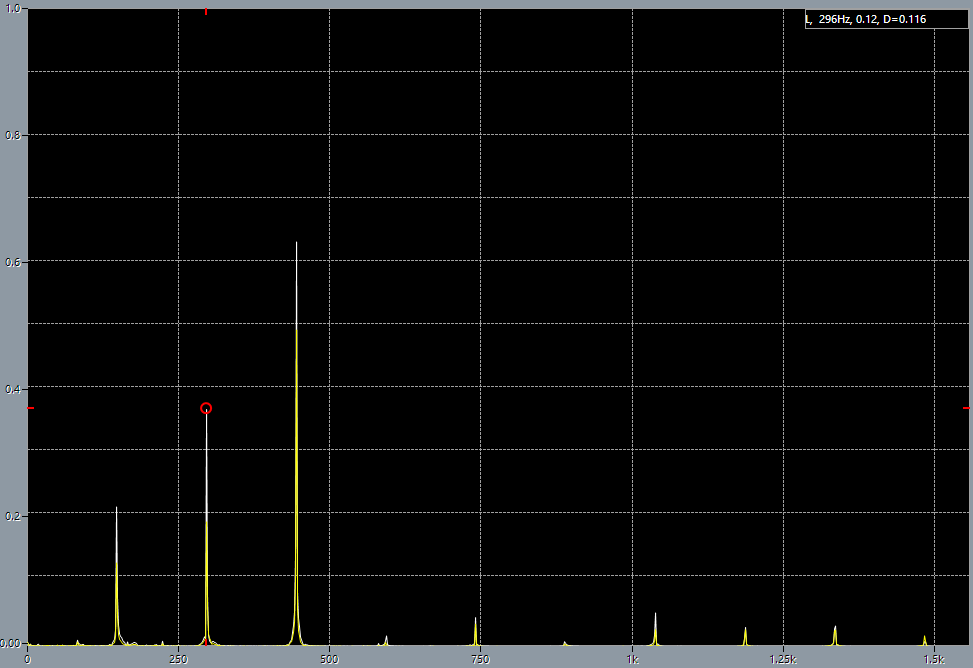

1st string before adjustment.

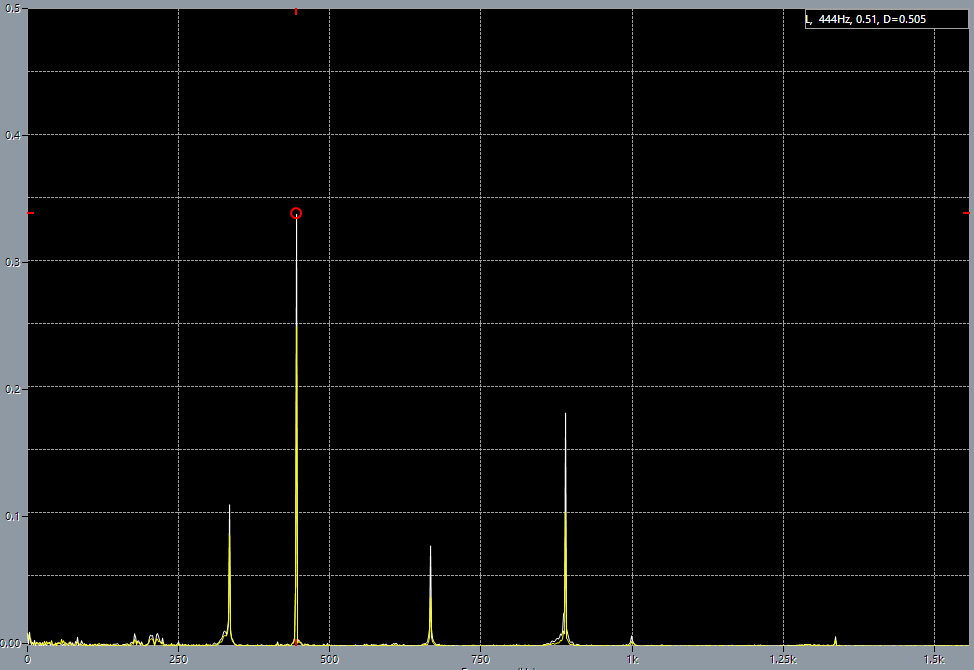

1st string before adjustment. 1st string on 5th fret before adjustment, base frequency 444 Hz.

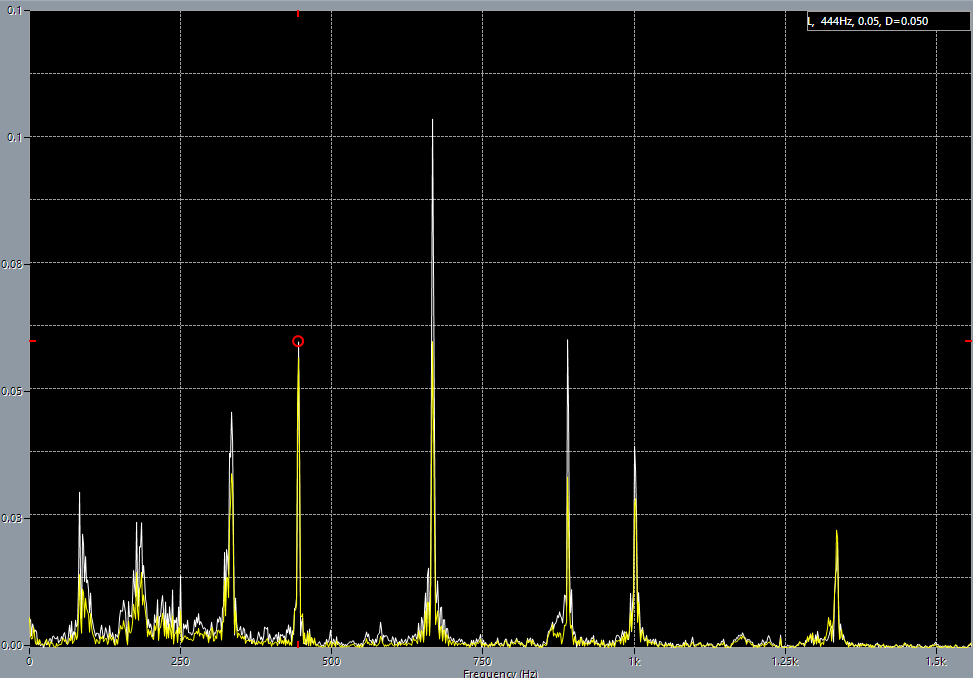

1st string on 5th fret before adjustment, base frequency 444 Hz. 1st string on 5th fret after adjustment.

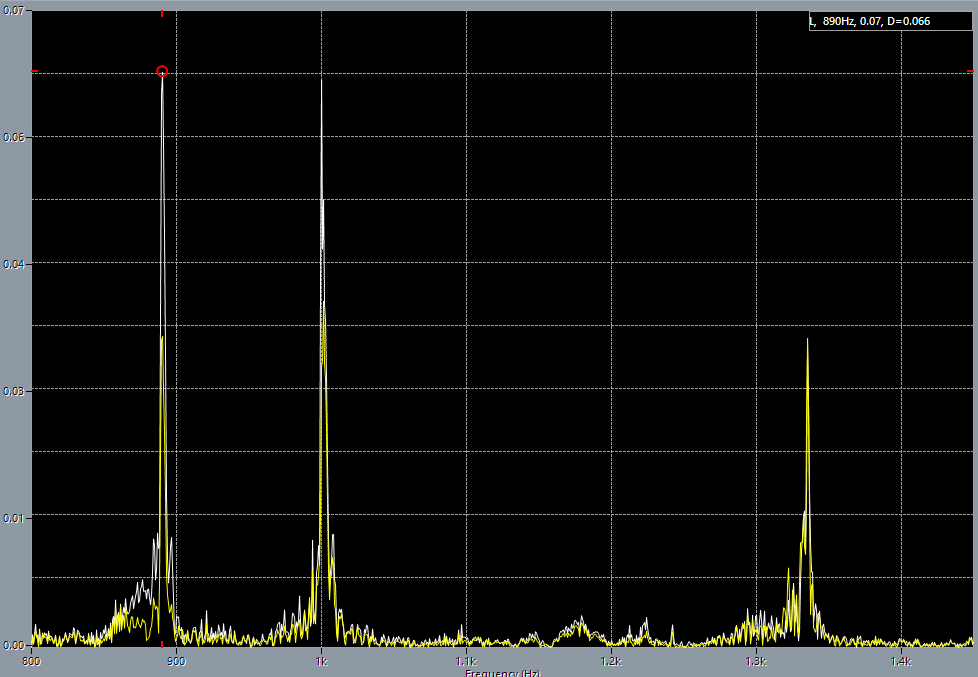

1st string on 5th fret after adjustment. 1st string on 5th fret after adjustment, 890 Hz base tone.

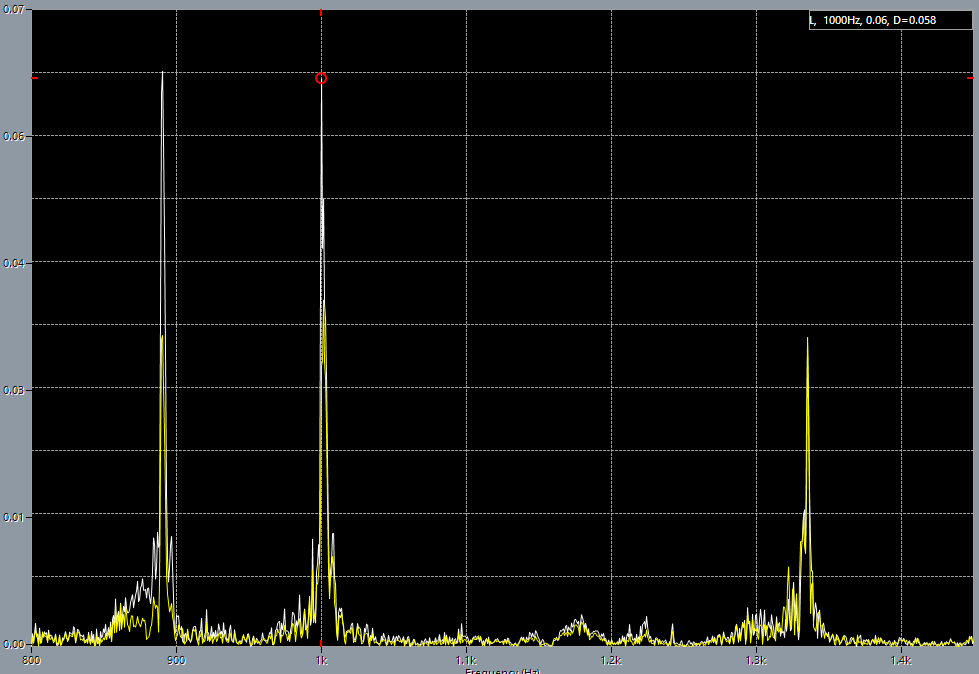

1st string on 5th fret after adjustment, 890 Hz base tone. 1st string on 5th fret after adjustment, 1000 Hz harmonics.

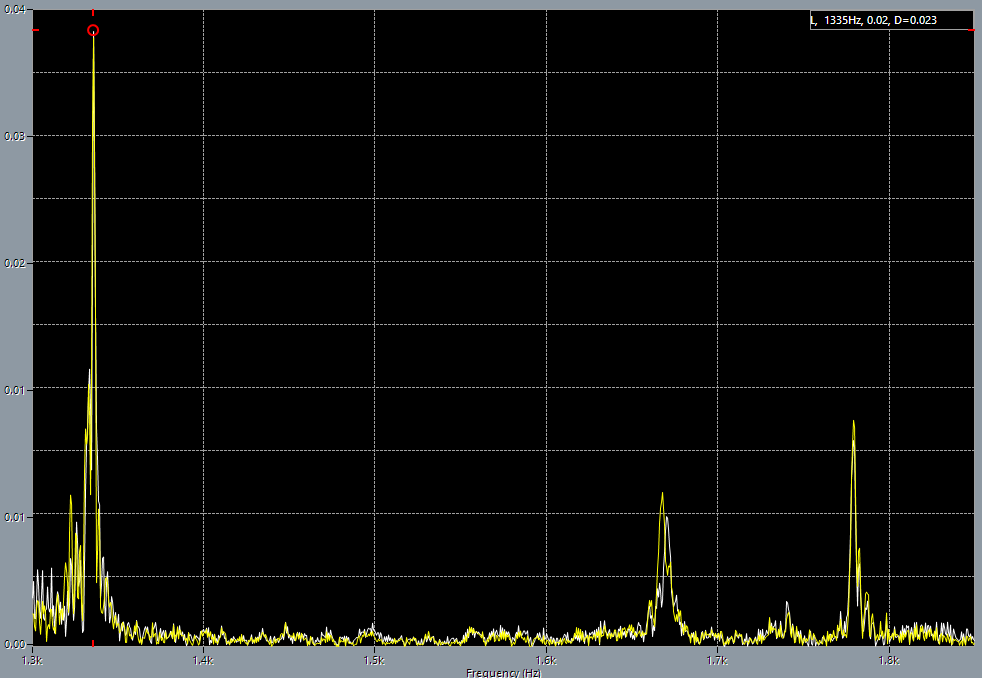

1st string on 5th fret after adjustment, 1000 Hz harmonics. 1st string on 5th fret after adjustment, 1335 Hz harmonics.

1st string on 5th fret after adjustment, 1335 Hz harmonics. 2nd string before adjustment.

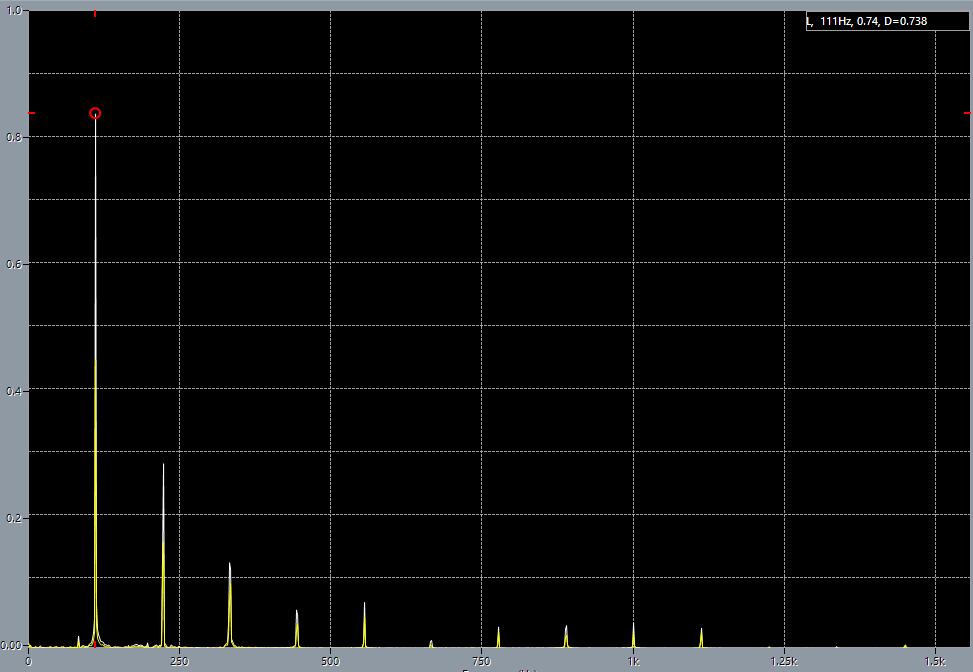

2nd string before adjustment. 3rd string before adjustment.

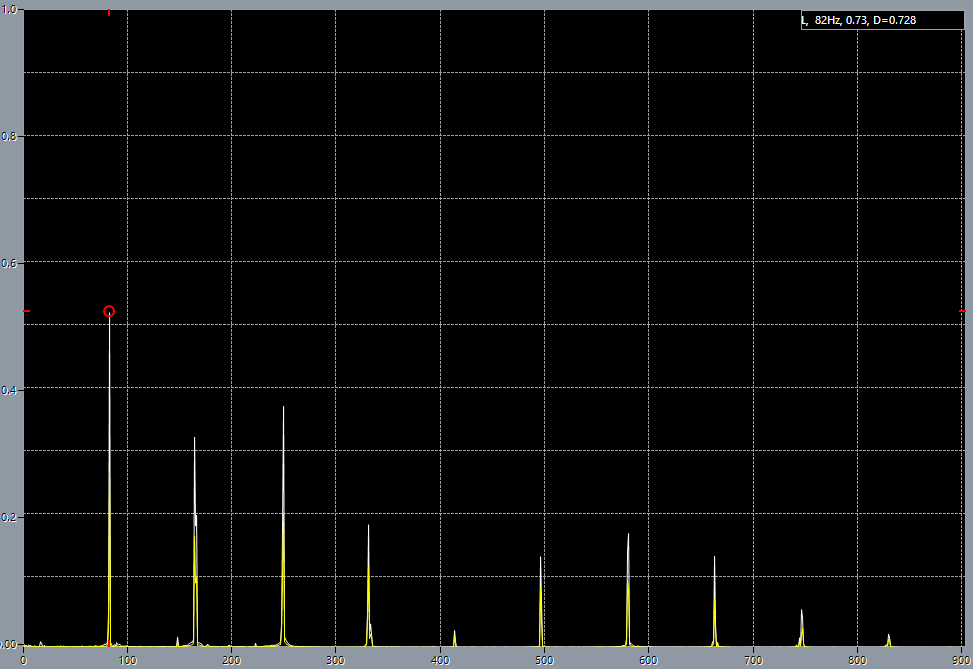

3rd string before adjustment. 4th string before adjustment.

4th string before adjustment. 5th string before adjustment.

5th string before adjustment. 6th string before adjustment.

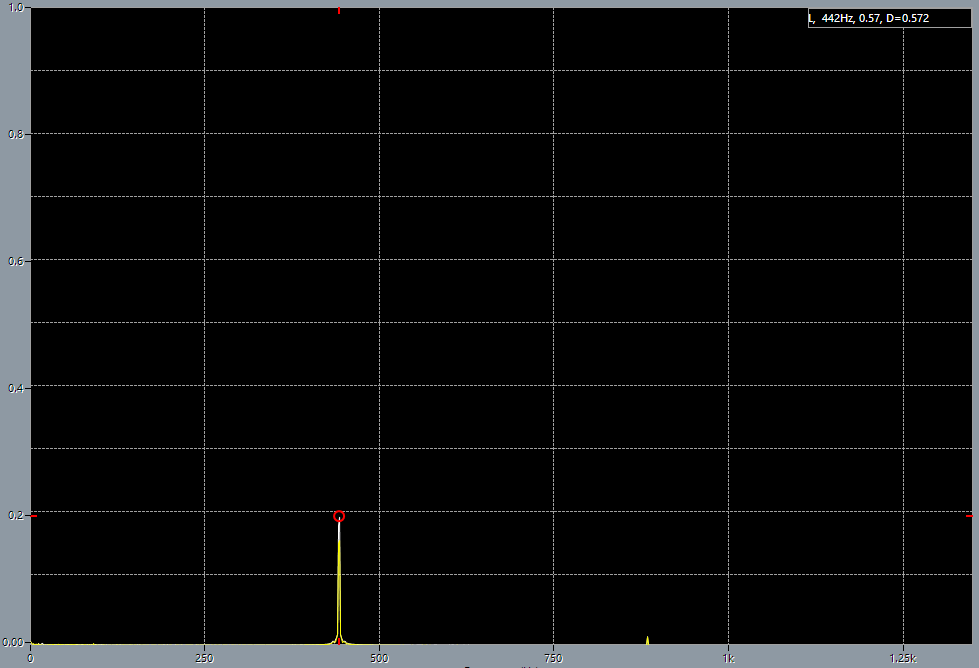

6th string before adjustment. A-440 tuning fork.

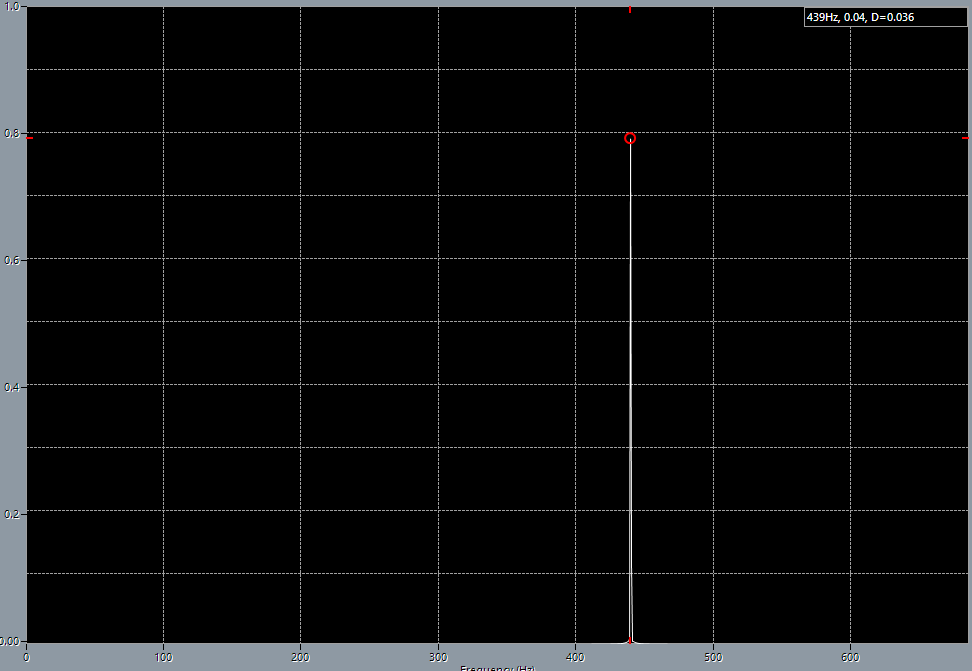

A-440 tuning fork. Pure sine 440 Hz, generated by Audacity, after resampling from 48 kHz to 44.1 kHz.

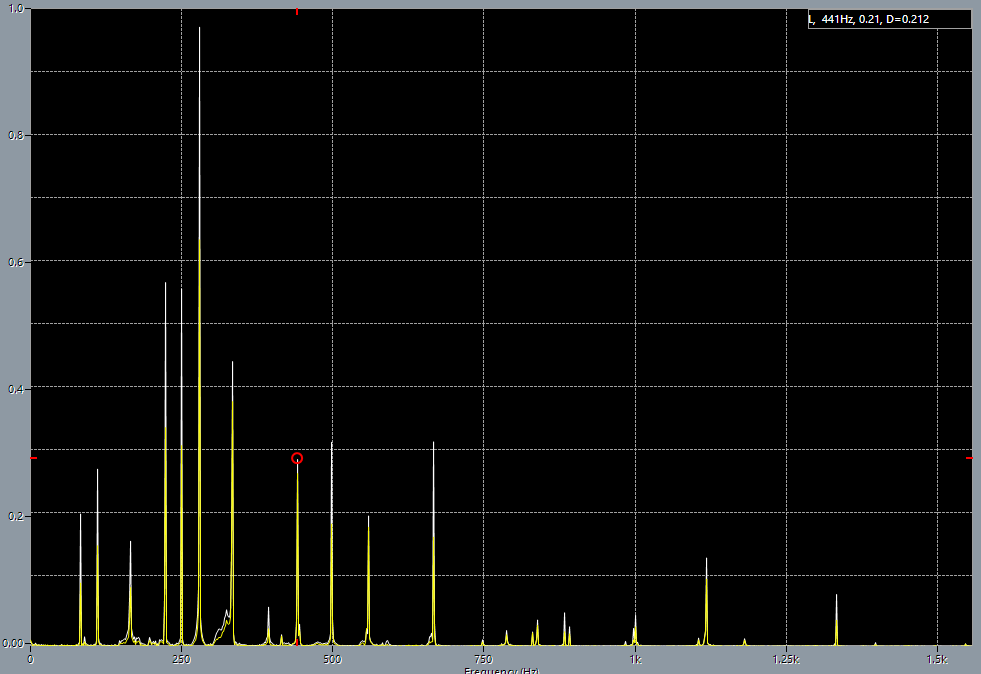

Pure sine 440 Hz, generated by Audacity, after resampling from 48 kHz to 44.1 kHz. A major chord in open position after adjustment.

A major chord in open position after adjustment.Try it! Develop your hearing, do not be lazy!

As can be seen from the spectrum pictures, exactly 440 Hz did not appear after the adjustment. On the contrary, the tuning, according to the computer, got worse: there were 887 Hz (+7 Hz) before the tuning, and it became 890 Hz (+10 Hz) after tuning! But everything becomes allright if I provide the computer to analyze A major chord, played in open position, after adjusting. The difference from the tone of the tuning fork is only 1 Hz, with the error that Cubase states it has, in maximum quality of FFT, as 0.37 Hz. But in fact since the Cubase scale does not display fractional hertz, I fit into measurement error of the equipment.

The conclusion is: we recognize a note not only and not even by its main tone, but as a combination of harmonics and their amplitudes. Bad news for the autotuners.

Automated translator was used to help make this article available in English.